Thinking

Salvaging our history: Lessons on circular economy implementation

Kimberley Ertl, our Senior Consultant, reflects on her experience tackling material salvage while on her ten-month secondment with Sir Robert McAlpine at the Museum of London. Joining the project as an Engineer and Package Manager, she quickly saw an opportunity to scale up material reclamation and went all in.

“This would be so much easier if we knocked it down and started again”

– a phrase I’ve heard on numerous sites and projects.

The construction industry is very good at building new. As designers and engineers, we’re most comfortable when sat in our offices running calculations that start from a blank page and introducing ‘new stuff’. We can confidently cost new stuff, plan the delivery of new stuff, and are excited to put our names to shiny new stuff at the end.

Since my return to Expedition Engineering, I’ve hung up my hardhat and boots and am now working on embedding circular economy (CE) design principles into very early-stage strategic masterplans. With the benefit of time, I realise how my secondment taught me a serious amount about how to consider and derisk our ambitious CE strategies. Having worked alongside a team putting other designers’ ideas into action, I was fortunate to learn some of the practicalities of site work and the blockers that can make our proposals unimplementable. I’m now putting my experience to use, embedding practical solutions at the beginning of the strategic stage to ensure our ambitions can be delivered when these projects get to site.

My experience wasn’t unique; I experienced many of the common barriers cited as preventing reuse across the industry. I discovered just how challenging it is to try and overcome these, especially given how linked they are to the way projects are run. Reflecting back, I’ve captured the key lessons from my successes and failures in the hope they resonate, reassure, or help someone else exploring reclamation; either in your back garden or on a multimillion-pound construction site.

Image gallery

Circular economy needs a champion

CE needs a champion (or two!) in every key project team, at every project stage. As designers, it isn’t good enough to sneak clauses into Employer’s Requirements or add notes on drawings without fully exploring what it means on site. We can’t expect demolition contractors to suddenly know how to find a viable route to rehome materials that have previously been considered of ‘no value’ – we must allocate people power to inspire and unlock our circular ambitions!

Champions are especially needed on site to remind everyone of the positive impact they can have if they give a little extra (from reducing waste, helping a charity organisation and / or removing the need for new virgin material) – especially when we’re already stretched for time and energy, and there isn’t always monetary gain to be made. Salvage is extra challenging in adversarial environments where cost is the main measure being tracked. It’s important to remember that we’re asking people to do something new and sometimes slightly off scope. This could be spending extra time demounting fixtures that would have previously been ripped down and finding a safe space to be stored, or sparing a moment to help load a van for a charity collection. We must value, recognise, and thank those putting in the effort behind the scenes to make reuse happen.

When is waste not waste?

I’ve stopped referring to existing material as ‘waste’ as a default. After all, it was clearly useful before! These kind of immediate classifications can complicate the processes and material tracking required on site. It also changes the perception of the material – from how it’s handled to how we frame reclaim opportunities.

For London-based projects, CE targets are aligned with the Greater London Authority requirements, including a minimum 95% diversion of waste from landfill. The framing of waste in this target means it must be cleared from site and handled by a waste specialist. If reclaim buyers / donors are found, it’s more challenging to divert these materials as many reclaim organisations don’t have the handling credentials, which in turn negatively affects the target. Whilst the requirements have good intent, most would agree that reuse is a preferable route than incineration – which is the current industry standard practice ‘diversion’ route.

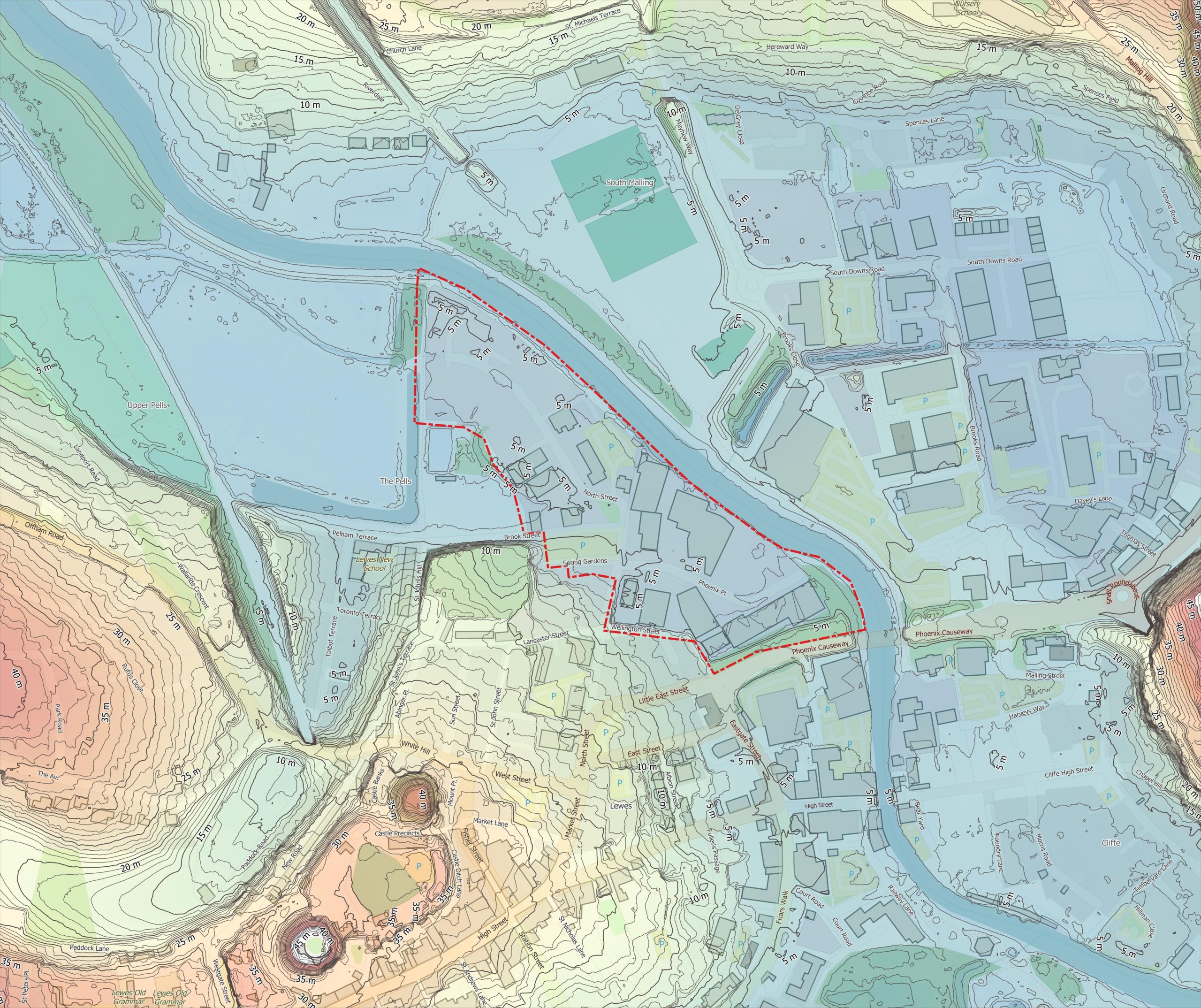

At the Museum of London (MoL), the scheme consisted of the part-demolition, repair, refurbishment, and extension of the existing General Market and Poultry Market buildings to create a new state-of-the-art facility in West Smithfield. This was a great place for me to see firsthand the state of material after various forms of demolition and how they are then handled – not an everyday experience in a design consultancy role. I was lucky that retention and reclamation were at the heart of the client’s design vision, and were embedded in the project’s planning requirements. As such, Stanton Williams, Julian Harrap Architects, and the wider project team had issued some unique additional resources to ensure materials for reclaim were identified in a salvage itinerary and specification; forming part of the demolition package.

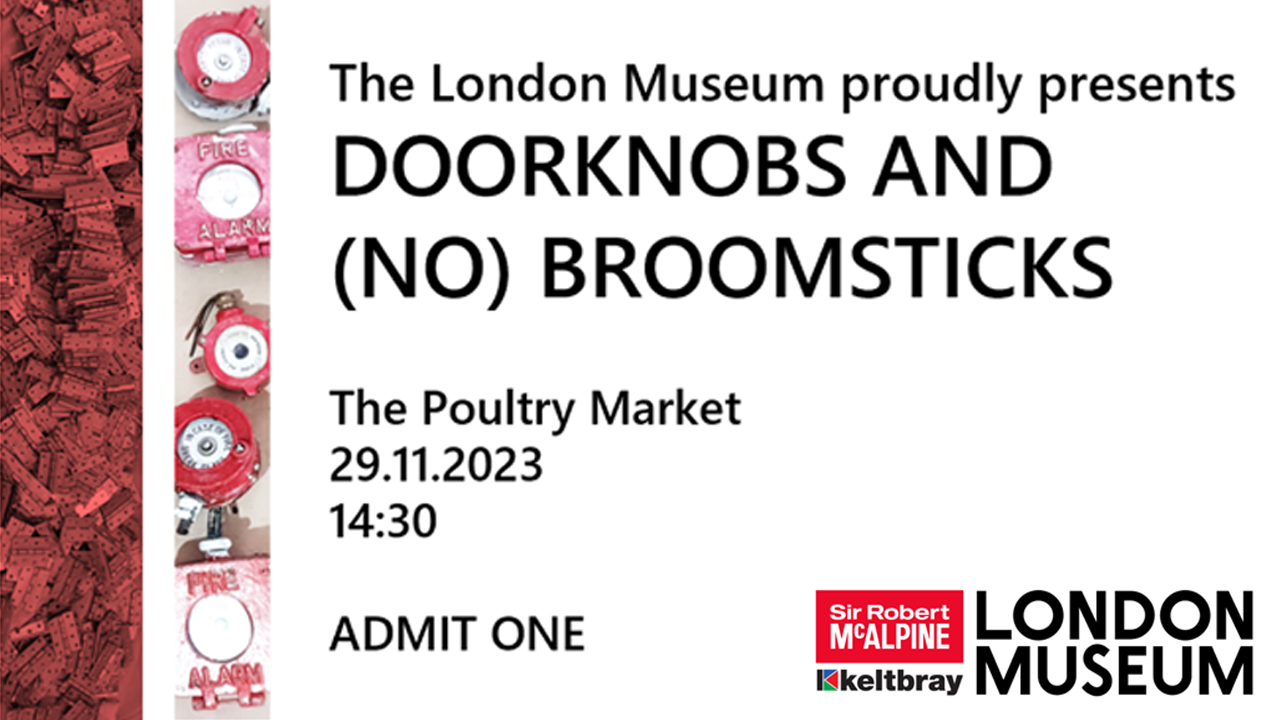

Working with Keltbray, the demolition contractor, we developed a Salvage Strategy for Poultry Market to save as many of the existing materials as possible, either for reuse in the final scheme or to sell and donate on the salvage market. Salvaged fittings and finishes were stored on site, and I then arranged a ‘salvage exhibition’ for the more special pieces. Laying out doorknobs, original brass switches, butler sinks, and retro fire alarms for review by curators, collectors, and curious passers-by enabled pieces to be selected for reuse in the final building, and those left behind were photographed and shared to find a new home.

One man’s trash is another child’s treasure

Having reclaim as a key project driver meant the demolition contractor knew at tender stage to allow for salvage in their works. It also meant we were talking about ‘material’ rather than ‘waste’, so the demolition arisings retained their value and, as a result, more material than usual could continue to be valued.

Successful demonstration of waste reuse changed mindsets at the MoL too. After seeing materials being collected by reuse organisations, other contractors began asking if they could use the next timber arisings to help in their work on site; it quickly became material, not waste.

The highlight of my secondment was seeing some seriously ‘waste-y’ material find a fun new home. Through my network at Expedition and the Useful Simple Trust, I connected the project team with Yes Make, a London-based design and build collective specialising in circular construction practices and community-focused projects. They were delighted to accept a donation of odds and ends from the Market basement, including salvaged timber, switches, door hinges, and other fittings. A few months down the line, these were transformed as part of a gorgeous new playground at Carpenter’s Estate in Stratford.

Be clear about the challenges

Demonstrating a small bit of reclaim on site helps change mindsets around the feasibility of reuse, but we have to be clear that there are risks involved in salvaging material. It’s essential to identify the chain of custody for materials as well as recognising who holds the risk and cost of disposal if a transfer falls through. Clients need to be informed of the programme implications for saving materials, and the logistics required in storing them for installation further down the line.

Market changes mean that value can vary from one day to the next, affecting the viability and financial risk of salvage on sites. Changes in the quality, quantity, and properties of deconstructed materials from what was anticipated in the pre-demolition audit can also suddenly make the additional cost of deconstruction unprofitable or, in our case, mean that timber sections we’d salvaged couldn’t serve their intended use for a reuse partner as they were all a little too short.

So, what next?

Currently, the gap between producing a ‘compliant’ CE statement and building a truly ‘circular’ development feels big. Looking ahead, I hope we can spend more time working up strategies that unlock the implementation of reuse schemes, rather than those that meticulously calculate the anticipated recycled content of a future project based on industry benchmark data. Our efforts should be spent identifying the opportunities presented by a particular project, connecting with others in reuse networks who could make them happen in practice, and developing contractual arrangements that reduce everyone’s exposure to risk.

I’m excited to see how, across the industry, we are increasingly exploring opportunities for reuse (whether we succeed or not) and learning from our attempts. I also can’t wait to see the MoL when it’s complete, delivering an exciting collection of new spaces in an old building that would not have had half as much character if we’d ‘simply’ “knocked it down and started again”.

Interested to learn more about what more you could be doing to prevent unnecessary material waste on site? Contact Kimberley Ertl at kimberley.e@expedition.uk.com.